Contribution By Laura Eley, Tucson, Arizona

Why Woodcut?

![By Jost Amman.AndreasPraefcke at de.wikipedia [Public domain], from Wikimedia Commons](https://woodadvocate.files.wordpress.com/2014/12/formschneider.jpg?w=230&h=300)

By Jost Amman.AndreasPraefcke at de.wikipedia [Public domain], from Wikimedia Commons

When learning about art styles in pictures books, I was drawn to the styles that involved woodcut illustrations. I decided to further my understanding through researching the general history of woodcut illustrations and by creating my own. Woodcuts are relief printing, where the part you want printed is left on the block, and the rest is cut away. Some common types of wood for woodcut illustrations are cherry, maple, beech, boxwood, and basswood.

Japanese Woodcut

Like so many art forms to come out of Japan, woodcut illustrations have a unique quality, and learning to do it requires careful study, the use of proper tools, and learning the long history. I have neither the patience, the tools, nor a teacher to show how me to do proper Japanese woodcuts, (or Ukiyo-e), so I focused my research and work on a western style of woodcut. But it is good to have a little background so we can see how western woodcuts differ.

![By Kaigetsudō Dohan (http://visipix.dynalias.com) [Public domain or Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://woodadvocate.files.wordpress.com/2014/12/kaigetsudo_dohan_-_bijin.jpg?w=160&h=300)

By Kaigetsudō Dohan [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Japanese woodcuts have a long history. They were used as a medium for reproduction of sanctioned images dating from around A.D. 740.[4] What we now consider traditional Japanese woodcuts rose to prominence in the 1600’s, when artisans began to rebel against the tight control of the shogun and make images of everyday life, including women of the brothels.[1] By the 19th century, Japanese woodcuts were so commonplace, they wouldn’t have been considered art at all.[3] In a time before photography, woodcut printing was the best mass-media illustration technique.

In Japanese woodcut, there are many people needed to create the image. A designer, a publisher, a carver, and at least one printer. The following website has a very interesting and complete history of Japanese woodcut, as well as techniques, tools, and material recommendations: http://woodblock.com/encyclopedia/index.html

Western Style

Western woodcuts not only have different subject matter and cutting techniques than Japanese, they also use different tools. The basic western-style tools are chisels for cutting out large surfaces and gouges to make finer lines.

The earliest western woodcut prints date from the early 1400’s. These were largely religious iconography, particularly souvenirs from pilgrimages; and playing cards.[3] Woodcut-printed playing cards were very popular, as they allowed many cheap prints to be made, making playing cards affordable to commoners. Germany, France, and Austria were the most prolific producers of woodcuts from this time, with Italy quickly joining in.[4] Block-books were created before the invention of moveable type, which were an illustration and text cut from a single block of wood.

![By Ernst Würtenberger (1868-1934) ("Schweizerland", vol.5 Nr. 9/10, 1919.) [Public domain or Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://woodadvocate.files.wordpress.com/2014/12/romeo_und_julia_auf_dem_dorfe_1.jpg?w=300&h=260)

By Ernst Würtenberger (1868-1934) (“Schweizerland”, vol.5 Nr. 9/10, 1919.) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

As moveable type became common in the mid-15th century, woodcut illustrations that were to accompany text began to have a standard height of 7/8″ so that it could be printed in conjunction with type.[5] Books illustrated with woodcut prints began to become popular, but the tools and techniques were still quite rudimentary. These prints were fairly basic, and were often painted in by hand to enhance the image. As demand for books grew, woodcut techniques in the west became more refined, and were able to be left uncolored, as the artists mastered techniques of gradation and suggestions of texture.[4] Some woodcuts were meant as art for art’s sake, but many of the woodcuts that survive from the 1400-1600’s survive as illustrations in books.

In contrast to the Japanese view of woodcuts at popular culture, in the west they were generally recognized at artwork. However, the artist was often not the person who actually cut the wood. As in Japanese woodcut, there was a division of labor, and the artist would give his design to a cutter, who was in the same low-class guild of craftsmen as carpenters.[3] Any woodcutters that would have designed their own art would have still been seen as lowly craftsmen, and their work was often left anonymous.

By the end of the 16th century, woodcut declined in usage for books as other methods, such as engraving, gained in popularity. Woodcut in general, and woodcut illustrations in particular, are so rarely seen throughout the next 400 years, that there are few records of published works in this time period.[4] In the late 1800’s, woodcut begins to experience a revival, as something of a niche style, used in fine quality, expensive books. The artists of the modern woodcut both design and cut the wood, which is a change from the days when woodcut illustrations were simply a commercial media – now they are an art.

Picture Book Woodcuts and Illustrators

In the west, woodcuts were used almost from the very beginning to illustrate books. Picture books of the modern age are occasionally illustrated with woodcut prints, particularly for books that portray nature or a simple life. Below I will give some brief information and links to some current children’s picture book illustrators that use woodcut illustrations.

Mary Azarian is a modern woodcut artist, and she has illustrated over 50 children’s books in this style. Her illustrations are classic Americana, and reflect her background. She taught in a one-room schoolhouse in Vermont, and used woodcut to create an alphabet book for her students. She won a Caldecott in 1999 for Snowflake Bentley. She also enjoys making woodcut art and has lots of examples on her website. http://www.maryazarian.com/about.html

Erin E. Stead is another modern picture book illustrator that uses woodcut. Her style is very different from Azarian’s, and is not particularly nature-themed. She won the Caldecott in 2011 for A Sick Day for Amos McGee. Her technique is to carve the shape of whatever she is drawing (for example, and elephant), print it with colored ink, then draw on top of it in pencil to add detail.[2] Examples of her work are available at her website. http://erinstead.com/

These illustrators show the variety that can be brought to picture books by woodcut illustrations.

My Process and Examples

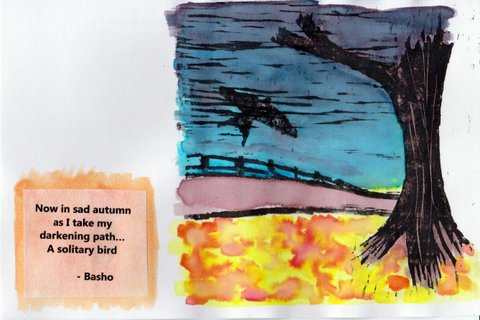

To learn how to do woodcut illustrations, I started small, with simple images and pieces of basswood. The reliefs became easier after practice and watching videos on technique. I carved and made a print of an oak leaf. After the ink had dried, I colored it with watercolor. I decided I wanted to illustrate something simple, small, and about nature. I feel that woodcuts really lend themselves to nature scenes. So I chose a haiku by Basho for my subject:

“Now in sad autumn

I take my darkening path,

a solitary bird.”

Here is my final illustration:

The path is carved in basswood. The bird is carved in cherry. The cherry was very difficult to carve. The sky and tree are in pine. All the elements are carved in separate pieces of wood. I printed the tree first, then the sky and path, and finally added the bird. All were printed with black water-based ink. When the ink dried, I painted over it in watercolor.

I enjoyed learning to do woodcut illustrations, but it was very difficult. I am impressed with how the old masters achieved such detail in their woodcuts.

Footnotes

[1]Bull, D. (n.d.). David Bull’s Encyclopedia of Woodblock Printing. Retrieved from David Bull’s Encyclopedia of Woodblock Printing: http://woodblock.com/encyclopedia/index.html

[2]Danielson, J. (2009, July 5th). 7-Imp’s 7 Kicks #122: Featuring Up-and-Coming Illustrator, Erin Stead. Retrieved from Seven Impossible Things Before Breakfast: http://blaine.org/sevenimpossiblethings/?p=1723

[3]Diehn, G. (2000). Simple Printmaking. New York: Lark Books.

[4]Hind, A. M. (1935). An Introduction to the History of Woodcut. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

[5]Leighton, C. (1932). Wood Engraving and Woodcuts. London: The Studio Ltd.

[6]Thompson, W. (2003, October). The Printed Image in the West: Woodcut. Retrieved from The Metropolitan Museum of Art: http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/wdct/hd_wdct.htm

Very cool! I especially like your leaf and the colors you choose. The solitary bird picture turned out nicely too.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks! – Laura

LikeLike